To my mind there's a certain value in utilitarian design in and of itself: as a frustrated mechanical engineer, born without a math gene (hence my diversion into the life sciences) but a strong sense of what is fitting and right, the concept of "form following function" has always had a powerful hold on me. Consequently I have a strong affection for plain-vanilla, work-a-day guns. Of course, I like all guns and deeply appreciate the beauty of the high-dollar ones, but there isn't anything I might do with a $2000 or $20,000 gun that can't be done with a $200 one. Utility-grade guns are...I don't know what the word is."honest" I guess. They're tools, and generally, as is true of most well-designed tools, there isn't anything on them that is not devoted to the purposes they are intended to serve.

To my mind there's a certain value in utilitarian design in and of itself: as a frustrated mechanical engineer, born without a math gene (hence my diversion into the life sciences) but a strong sense of what is fitting and right, the concept of "form following function" has always had a powerful hold on me. Consequently I have a strong affection for plain-vanilla, work-a-day guns. Of course, I like all guns and deeply appreciate the beauty of the high-dollar ones, but there isn't anything I might do with a $2000 or $20,000 gun that can't be done with a $200 one. Utility-grade guns are...I don't know what the word is."honest" I guess. They're tools, and generally, as is true of most well-designed tools, there isn't anything on them that is not devoted to the purposes they are intended to serve.

Guns are certainly female, when you consider them in abstract terms, sharing numerous attributes with women. Both guns and women are expensive to acquire and maintain; both are a lot of fun to fool around with; both use powder; some are more interesting than others, but none are wholly uninteresting; you can never have too many of either; and both will kill you if you handle them incorrectly.

While I admire beautiful women (in a perfectly respectful and detached sense of course) even if I weren't married I'd not make any effort to acquire one (or more) for myself. They're marvelously decorative-works of art, really-but not any more.er.ahem.useful than less-blessed ladies might be. I appreciate beautiful women in the same way I would a pack of sleek and comely tigresses: from a safe distance.

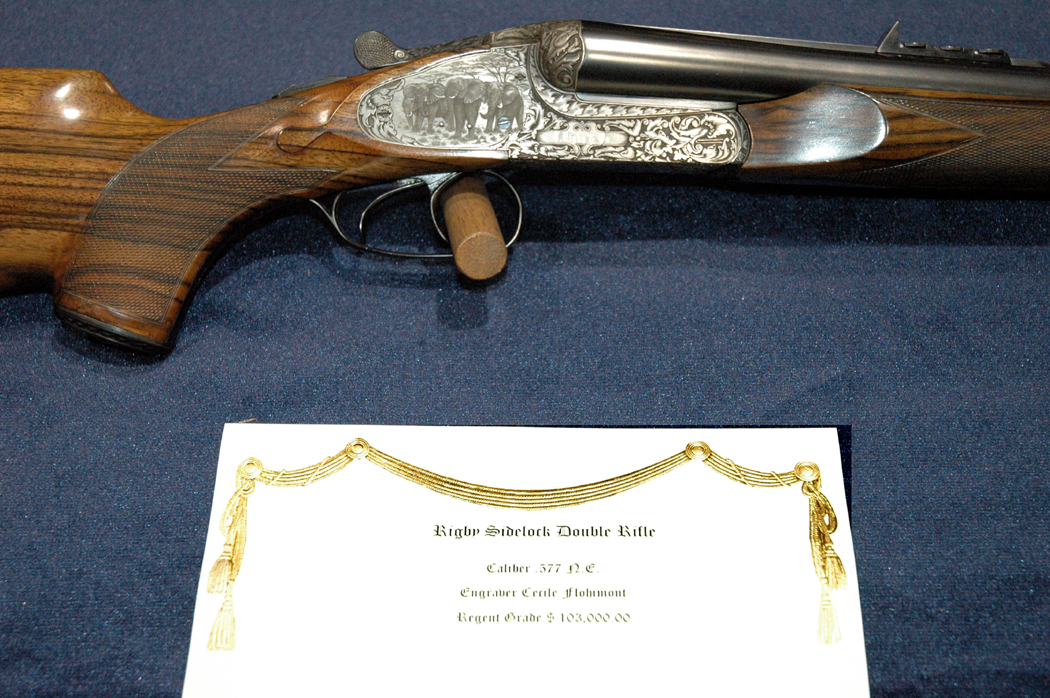

Similarly, while I'd certainly like to own a custom-fitted Purdey or Dickson shotgun or two, I'm not about to take such a firearm out in my boat or into the woods. I once went to the Safari Club International Show in Nevada, and there, on a pedestal (where it certainly belonged) was the Rigby double rifle shown at left, going for the fire-sale price of $103,000. Now, that's more than I paid for my house: there was NO WAY I was going to handle that gorgeous piece of hardware lest I damage it. Or grow too fond of it. Not even in my most hysterical fit of rationalization could I ever justify spending that much money when deer and squirrels can't tell the difference between a Rigby and a Mossberg. That's why my hunting is done with Savages, Mossbergs, and Marlins.

Similarly, while I'd certainly like to own a custom-fitted Purdey or Dickson shotgun or two, I'm not about to take such a firearm out in my boat or into the woods. I once went to the Safari Club International Show in Nevada, and there, on a pedestal (where it certainly belonged) was the Rigby double rifle shown at left, going for the fire-sale price of $103,000. Now, that's more than I paid for my house: there was NO WAY I was going to handle that gorgeous piece of hardware lest I damage it. Or grow too fond of it. Not even in my most hysterical fit of rationalization could I ever justify spending that much money when deer and squirrels can't tell the difference between a Rigby and a Mossberg. That's why my hunting is done with Savages, Mossbergs, and Marlins.

Of all the types of utility grade guns, I like shotguns the best, especially bolt action shotguns. The bolt action shotgun is the poor relation of more elegant sporting weapons. It's more or less an American phenomenon, though it has distinctly European roots and first evolved in Europe.

The bolt action per se is a European concept, dating to the middle 19th Century in its earliest forms, the famous Prussian "Needle Gun" and the early Vetterli series. The US Army was slow to adopt the bolt action. Various European nations had adopted bolt action rifles using fixed ammunition as early as 1869, but it took until the turn of the 20th Century for the US Army to catch up, with the adoption of the Model 1903 Springfield (a modified Mauser). Oh, sure, they'd performed a few half-hearted trials with Lee's designs in the 1870's, and eventually adopted the Krag (designed in Norway) as a short-lived general-issue rifle in 1892, but they stuck with the reliable Trapdoor Springfield for nearly 40 years: Trapdoors were still being issued to militia, National Guardsmen, and some reservists as late as 1914!

The bolt action per se is a European concept, dating to the middle 19th Century in its earliest forms, the famous Prussian "Needle Gun" and the early Vetterli series. The US Army was slow to adopt the bolt action. Various European nations had adopted bolt action rifles using fixed ammunition as early as 1869, but it took until the turn of the 20th Century for the US Army to catch up, with the adoption of the Model 1903 Springfield (a modified Mauser). Oh, sure, they'd performed a few half-hearted trials with Lee's designs in the 1870's, and eventually adopted the Krag (designed in Norway) as a short-lived general-issue rifle in 1892, but they stuck with the reliable Trapdoor Springfield for nearly 40 years: Trapdoors were still being issued to militia, National Guardsmen, and some reservists as late as 1914!

It's axiomatic that whatever the military forces of a nation use is what becomes popular with sportsmen: all sporting guns are essentially derivatives of military designs. Because of the Army's neglect of the bolt action, they weren't really familiar to American civilians until just before the First World War. Some were indeed used by sportsmen: Sears and other mail-order houses sold surplus Vetterli rifles by the shipload in the period before World War One. The ad at left is from an old Sears catalog; even in 1902 that price of $7.25 was a colossal bargain for a very, very high quality rifle. Though hundreds of thousands were sold, they represented a very small fraction of the total market for sporting guns. The quintessential "American" sporting gun around the turn of the 20th Century was the lever action. A lever action rifle was a symbol of

It's axiomatic that whatever the military forces of a nation use is what becomes popular with sportsmen: all sporting guns are essentially derivatives of military designs. Because of the Army's neglect of the bolt action, they weren't really familiar to American civilians until just before the First World War. Some were indeed used by sportsmen: Sears and other mail-order houses sold surplus Vetterli rifles by the shipload in the period before World War One. The ad at left is from an old Sears catalog; even in 1902 that price of $7.25 was a colossal bargain for a very, very high quality rifle. Though hundreds of thousands were sold, they represented a very small fraction of the total market for sporting guns. The quintessential "American" sporting gun around the turn of the 20th Century was the lever action. A lever action rifle was a symbol of

Of course, change was inevitable. By 1918, well over a million men had passed through the Army's training camps, becoming familiar and comfortable with bolt action rifles. When the Doughboys came home from Over There in 1918, they represented a marketing opportunity.

Of course, change was inevitable. By 1918, well over a million men had passed through the Army's training camps, becoming familiar and comfortable with bolt action rifles. When the Doughboys came home from Over There in 1918, they represented a marketing opportunity.

The US arms industry had ramped up for war production but was faced with the stark fact that the war had ended just about the time they'd worked the kinks out of their mass production methods and were getting into high gear. They needed new products, and they needed them fast, to recoup their investment and stay in business. The first post World War One sporting gun products are no exception to the axiom that all sporting weapons are derivatives of military designs: Winchester and Remington quickly shifted their assembly lines to turn out modified M1917's in sporter dress, and smaller manufacturers began sniffing out opportunities too.

The exact date of the introduction of bolt action sporting shotguns is a matter of debate, but they originated in Europe, not in

Now,  only so many of these that the European market could absorb. The million or so "leftovers" were worth nothing more than scrap metal prices unless some way could be found to use them. Inevitably, many of them were modified into shotguns, which weren't "implements of war" as defined in the Treaty, and which could be produced without contravening it.

only so many of these that the European market could absorb. The million or so "leftovers" were worth nothing more than scrap metal prices unless some way could be found to use them. Inevitably, many of them were modified into shotguns, which weren't "implements of war" as defined in the Treaty, and which could be produced without contravening it.

Such inexpensive shotguns were sold in whatever markets could be found: among German citizens who needed a utility firearm, in various export markets, in ex-German colonies, and wherever an outlet existed. A few found their way to the

In those long-gone days there was hardly a home in

In those long-gone days there was hardly a home in

Shotguns were essential for shooting rabbits in the cabbage patch and groundhogs in the garden; for defending home and hearth, and occasionally for convincing a daughter's reluctant swain that marriage was a good idea. It is also worth remembering that almost as late as World War Two, anyone driving an automobile on a long distance trip didn't find a Quality Inn and a Wendy's every ten miles or so. They brought along camping gear. Among the items routinely carried along was a shotgun, just the thing needed to bag a rabbit for the pot while camping in a cornfield for the night.

Examining the mail-order catalogs of the post-Civil War to pre-World War One period is an enlightening exercise. Double shotguns are by far the dominant action type, sold at all levels of price and quality, most of them made in Europe. Hundreds of thousands-perhaps millions-of doubles had been shipped from Europe in before and after the Civil War to serve the needs of westward expansion and settlement, first into the Mississippi drainage and later on and across the Great Plains. American manufacturers selling to the utility gun market also provided low-cost break-actions, both single and double-barreled, in copious numbers.

So the stage was set for the emergence of the bolt action shotgun as World War One ended: such guns had been shown to be practical, and there was a significant market segment waiting to be served. In 1919, the newly-created and highly innovative firm of Mossberg opened for business.

So the stage was set for the emergence of the bolt action shotgun as World War One ended: such guns had been shown to be practical, and there was a significant market segment waiting to be served. In 1919, the newly-created and highly innovative firm of Mossberg opened for business.

Mossberg has always had a reputation for thinking outside the box, and for serving the entry-level sporting gun market with reasonably priced, dependable guns. It was perhaps inevitable that Mossberg would introduce the bolt action shotgun to America: and do so at a time of great economic turmoil.

Mossberg has always had a reputation for thinking outside the box, and for serving the entry-level sporting gun market with reasonably priced, dependable guns. It was perhaps inevitable that Mossberg would introduce the bolt action shotgun to America: and do so at a time of great economic turmoil.

Rather than adapt an existing action, Mossberg chose to design an entirely new gun, one that could be quickly produced at low cost. "A Single Shot bolt action to meet the increasing demand for a really good shotgun at a popular price," as their ad copy puts it, is an admirably succinct description of the first Mossberg bolt action shotgun, the Model G in the then-new chambering of .410 bore. It was introduced in 1932, became a success and was followed with new and improved versions in various gauges over the years.

Even though they hit the

Mossberg made bolt action shotguns in popular gauges for many years, with their guns also selling not only under their own label, but under the house brands of Sears, Ward's, Western Auto, and lesser-known chains. Production of Mossberg bolt action shotguns continued in some form or other into the 21st Century. One of the latest descendants of the Model G is the Model 695, a specialized gun for turkey and deer hunting.

Mossberg made bolt action shotguns in popular gauges for many years, with their guns also selling not only under their own label, but under the house brands of Sears, Ward's, Western Auto, and lesser-known chains. Production of Mossberg bolt action shotguns continued in some form or other into the 21st Century. One of the latest descendants of the Model G is the Model 695, a specialized gun for turkey and deer hunting.

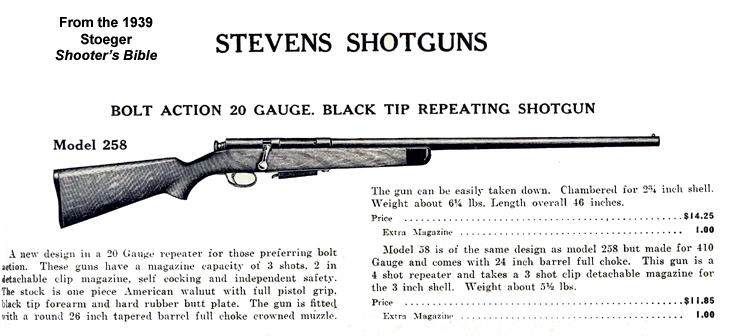

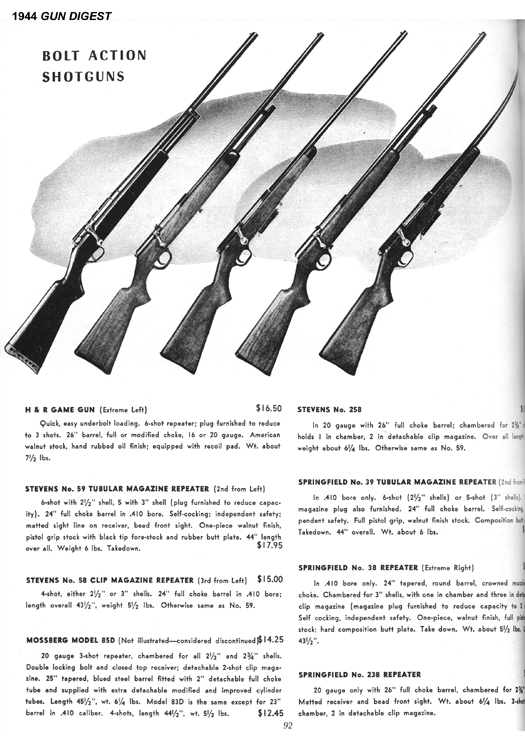

Mossberg's success inevitably meant they were soon followed by other utility-gun makers such as Stevens. By the early 1930's bolt action shotguns represented a small but significant share of the utility-gun market. By 1939, Stoeger was listing four or five Stevens made bolt actions in their yearly catalog, The Shooter's Bible.

Mossberg's success inevitably meant they were soon followed by other utility-gun makers such as Stevens. By the early 1930's bolt action shotguns represented a small but significant share of the utility-gun market. By 1939, Stoeger was listing four or five Stevens made bolt actions in their yearly catalog, The Shooter's Bible.

The farmer whose old gun had worn out; the city dweller whose son wanted a “new” gun for Christmas: they could do far worse than one of these homely, unpretentious, but effective guns. A great many—perhaps most—of those between-the-wars bolt action shotguns are still around today, doing yeoman service for the grandchildren and great grandchildren of the men who bought them new. That, in and of itself, is a testimonial to their significance to the American sporting shooter.

I've owned a number of bolt action shotguns over the years. During my exile in Texas I bought a J.C. Higgins 16-gauge for all of $15. "J.C. Higgins" is one of the many "private label" brands found on guns, and was one of Sears, Roebuck's trademarks. The practice is pretty much defunct these days but at one time all the large retail houses bought guns from major makers and had them labeled with their own trade names. Sears, Ward's ("Hawthorne," "Western Field," "Hercules") and Western Auto ("Revelation") were the largest buyers but other  companies (Coast to Coast Hardware, Oklahoma Tire & Supply, Gamble's, and many smaller operations) did the same thing. Most private label shotguns were made by Mossberg or Savage, though not a few were made by High Standard and Harrington & Richardson. The guns are identical to the "name" branded guns except for the markings.

companies (Coast to Coast Hardware, Oklahoma Tire & Supply, Gamble's, and many smaller operations) did the same thing. Most private label shotguns were made by Mossberg or Savage, though not a few were made by High Standard and Harrington & Richardson. The guns are identical to the "name" branded guns except for the markings.

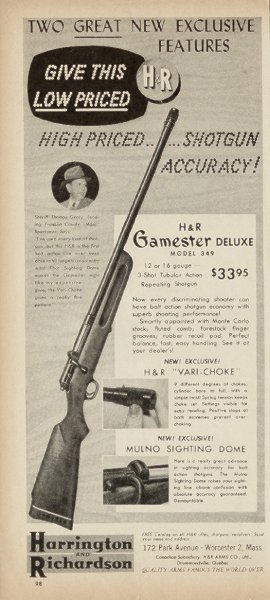

The one I bought later keyed out to be a Harrington & Richardson "Gamester," probably produced in the early 1950's. I took it home and cleaned it up, and lo, it had a nice piece of walnut on it! Not the "walnut-finished hardwood" used on cheap guns today: it came from a time when a blemished stock blank that couldn't be used on a "good" gun was relegated to the utility category, and all stocks were walnut. It sold brand new in the Sears 1954 catalog for $20, because it was a "deluxe" model with a Polychoke. After I got done refinishing the stock it looked so nice a graduate student offered me $70 for it, and I was unable to pass up the opportunity to almost triple my money. I've regretted that sale ever since, but I found another one (also a 16) that was not quite so nice, and still have it. It's my behind-the-truck-seat gun and my boat gun, the one I throw in the canoe when I'm fishing in case a ferocious woodchuck or squirrel comes by on the bank and threatens my fish or my life.

One day as I was walking into a gun shop I met a man coming out who had a Mossberg 185 in 20 gauge. This gentleman was seriously annoyed with the shop owner, who had refused to give him his asking price for the gun—$40—because it had a Polychoke on it. "...I cain't sell no gun what has that great big dog-nut hangin' off the barrel!" the shop owner had said. Offended by the miserable offer of $10, the honest citizen was delighted when I handed him two twenties on the spot, and took the gun (plus the case) with me.

The Model 185 was a genuinely hideous piece of hardware, but no Mossberg bolt action shotgun has ever won a beauty contest. It had the tacky black plastic trigger guard with the finger grooves, and the red and green plastic dots for the safety positions. My Uncle Mike who lived in Brooklyn owned one exactly like it. Uncle Mike had no money, lived in a white T-shirt, drank a lot of Schlitz, wore white socks, and was the role model for Archie Bunker. He had bought his to use when he went to visit a friend in the Catskills, but the only thing he ever shot with it was empty Schlitz cans. When he died it went to my sister's husband, who still has it.

I took that 1960's vintage clunker in hand, stripped and refinished the stock (alas, it was beech, not walnut) and touched up the blue where it had worn. It was in good mechanical shape, even though the magazine was full of crud and dirt, as it had never been disassembled. When I took the magazine apart, inside it was the original factory instruction slip on how to get the follower back in place properly! I eventually gave it to my wife's cousin, who owned a farm in Ohio where I used to hunt.

Stevens bolt actions, like Mossberg's, are enduring products, and frequently encountered today on auction sites. Stevens also made many private-label guns. Most of them are variants of the Model 58 or 59. In 1971 I was stationed at Andrews AFB, where a weekly newsletter advertised stuff for sale. There was an ad in it for a "Shotgun, brand new, no stock, $10.00." That one turned out to be a near-new Stevens 58H 12-gauge, minus the stock, as advertised.

The seller's brother-in-law had backed a truck over the gun and broken the stock clean across the wrist. All the metal parts were intact and in perfect shape, but the stock had been discarded; I could have the metal parts for $10 cash. I am not a fool and I have never passed up a ten-dollar gun in my life: I bought it and promptly ordered a brand-new stock from the factory for $15.

It also has a Polychoke, a feature that makes a lot of sense on single-barrel guns. I still have that Stevens. It has accounted for quite a bit of game. I used to hunt in a shotgun-only area of New York, so I had it fitted with rifle sights to use as a deer gun, and killed my first two deer with it. It shoots Foster slugs into 4" at 100 yards or so, more than good enough for my purposes. The stock has been refinished and looks much better than it did when Stevens sent it to me. I'll never sell it.

Though part of the appeal of bolt action shotguns is their homely looks, some are less homely than others. If any of them can be said to be "attractive" it has to be the Stevens series with box magazines. In the past few years my affection for my 12 gauge Model 58, coupled with my liking for the 20 as the perfect gauge for the squirrel hunter, led me to buy two Model 58's in that gauge. Both were going begging at low prices on Auction Arms, so I took the bait.

One of these two little guns has made two kills. The first was a squirrel and the second an unfortunate 4-point buck that had got himself hung up in a fence by his right hind foot as he tried to jump it. I was called by the farmer and asked to put the deer out of his misery, and the one without the Polychoke was at that moment in my truck, so did the deed. The one with the Polychoke is in near-new condition and I have yet to fire it.

I like to donate guns to our local Friends of the NRA Foundation annual event, especially guns that are suitable for young people. One or both of these will eventually go to that purpose. I have often regretted selling a gun, but never have I regretted giving one away.

I briefly owned a Mossberg Model 183K in .410. As much as I like the 20 gauge, I disdain the .410 as more or less the most useless shotgun shell on the market. I know that people think of it as the perfect starter gun for kids, but the truth is that a .410 is so feeble and throws such a small charge of shot that it really is a gun for experts, not beginners. The 183K was given to me by someone who'd learned the uselessness of the .410 the hard way, and was in exceptionally good condition. I took it, but had no real plans for it. It eventually was donated to the FONRA event and some kid was delighted to get it. That's fine by me: one more person who has a stake in The Cause. If that little Mossberg never does anything else but bring a new shooter into the fold, it will have been worth its cost.

What are bolt action shotguns good for? Well, more or less any upland application where a rapid second shot isn't needed. The introductory ad copy for Mossberg's Model G shows a hunter eyeballing geese that are at least 100 yards away! This is beyond wishful thinking, even if we make allowance for the exaggeration of an advertisement. An expert shot shooting over decoys at short range, might be able to use a .410 on waterfowl if he chose his shots, but one would surely need Divine Intervention to achieve a killing hit on a flying Canada Goose with any .410, let alone a bolt gun. Nor would I choose one for grouse, since fast handling is hardly their strong point. But for squirrels, rabbits, and maybe even pheasant, a bolt action works just fine.

The early bolt action shotguns tended to be single-shots, but repeating guns came out very soon after, and I don't think there are any single-shot bolt guns still being manufactured. The three-shot limit mandated for waterfowl by the Federal government in 1934 seems to have been the reason that virtually all bolt action shotguns hold no more than three rounds. This makes them less popular in places where the limit isn't imposed on upland game. The limit has never been a problem for me. Seldom do I need more than one shot for a squirrel, maybe two for a groundhog. In small game hunting it's irrelevant. With deer, a slug in the brisket puts the lights out instantly: I've personally known several deer shot with 12 gauge slugs and every one was an instant one-shot kill.

Bolt action shotguns have evolved into a sort of "niche" product, and one of the niches they fill admirably is in deer hunting. With the advent of the rifled "shotgun" barrel, several versions have been developed whose sole purpose is deer hunting, in fact. The most successful of these and the best known are the guns by Tar-Hunt. Tar-Hunt has recognized the inherent strength and stability of bolt actions that makes them more inherently accurate with single projectiles than pumps or autoloaders. Their guns are specialized deer-killing machines, and the newer

Bolt action shotguns have evolved into a sort of "niche" product, and one of the niches they fill admirably is in deer hunting. With the advent of the rifled "shotgun" barrel, several versions have been developed whose sole purpose is deer hunting, in fact. The most successful of these and the best known are the guns by Tar-Hunt. Tar-Hunt has recognized the inherent strength and stability of bolt actions that makes them more inherently accurate with single projectiles than pumps or autoloaders. Their guns are specialized deer-killing machines, and the newer  generations of sabot-style slugs, for which they're designed, are far more accurate than the old Foster-style slugs ever could be. Combining a strong action, rifle-style bedding, a good scope, and superior ammunition pushes the range of slug guns out to well beyond the 75-100 yards that has always been considered the limit of accuracy of shotguns. Tar-Hunt's guns are expensive but popular in many states where only shotguns may be used to hunt deer, as they give the hunter a real edge. They're not general-purpose guns, but they're not intended to be. Marlin and Mossberg also make models more or less in the Tar-Hunt style.

generations of sabot-style slugs, for which they're designed, are far more accurate than the old Foster-style slugs ever could be. Combining a strong action, rifle-style bedding, a good scope, and superior ammunition pushes the range of slug guns out to well beyond the 75-100 yards that has always been considered the limit of accuracy of shotguns. Tar-Hunt's guns are expensive but popular in many states where only shotguns may be used to hunt deer, as they give the hunter a real edge. They're not general-purpose guns, but they're not intended to be. Marlin and Mossberg also make models more or less in the Tar-Hunt style.

Cost, durability, versatility, all these are virtues. If you have a penchant for ugly guns, that doesn't hurt, either. As Benjamin Franklin remarked in a different context, "In the dark, all cats are gray." In the upland game field, a bolt action shotgun will serve you as well as a fancier gun, most of the time.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |